By Jamie Dimon, Chairman and Chief Executive of JP Morgan

Dear Fellow Shareholders,

2020 was an extraordinary year by any measure. It was a year of a global pandemic, a global recession, unprecedented government actions, turbulent elections, and deeply felt social and racial injustice. It was a year in which each of us faced difficult personal challenges, and a staggering number of us lost loved ones. It was also a year when those among us with less were disproportionately hurt by joblessness and poverty. And it was a time when companies discovered what they really were and, sometimes, what they might become.

Watching events unfold throughout the year, we were keenly focused on what we, as a company, could do to serve. As I begin this annual letter to shareholders, I am proud of what our company and our tens of thousands of employees around the world achieved, collectively and individually. As you know, we have long championed the essential role of banking in a community — its potential for bringing people together, for enabling companies and individuals to reach for their dreams, and for being a source of strength in difficult times. Those opportunities were powerfully presented to us this year, and I am proud of how we stepped up. I discuss these themes later in this letter.

https://twitter.com/Chase/status/1379765941504909324

III. Banks’ Enormous Competitive Threats — from Virtually Every Angle

To fairly assess the competitive landscape for banks, you must fairly evaluate their strengths and weaknesses to deal with both the current competition and evolving competition. Banks have significant strengths – brand, economies of scale, profitability, and deep roots with their customers and within their communities. Many companies, including banks, have flaws of their own making – usually due to bureaucracy, complacency and lack of a deep competitive spirit. Banks have other weaknesses, born somewhat out of their success – for example, inflexible “legacy systems” that need to be moved to the cloud if they are to remain competitive. Banks are also required to deal with extensive regulations, which can hinder new competition and/or create an opening for both existing and evolving competitors. Banks fiercely compete with each other and now face fierce competition from multiple vectors.

Banks already compete against a large and powerful shadow banking system. And they are facing extensive competition from Silicon Valley, both in the form of fintechs and Big Tech companies (Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google and now Walmart), that is here to stay. As the importance of cloud, AI and digital platforms grows, this competition will become even more formidable. As a result, banks are playing an increasingly smaller role in the financial system.

I am completely in favor of open competition, and much of the competition that I cover in this section will be good for America. One of the necessities for a healthy economy, and one at the core of America’s success, is a strong, vibrant financial system. The disciplined allocation of capital, and the constant search for new opportunities for capital, is critical to growth (a corollary of the free and intelligent movement of capital is the free movement of human talent, which, ultimately, may be even more important). America’s financial system is the best the world has ever seen, from our regulatory system and rule of law to exchanges, venture capital and private capital, banks and shadow banks. As our system changes, our government and regulators need to understand that maintaining the vibrancy, safety and soundness of this system is critical – and this includes maintaining a relatively fair and balanced playing field. While I am still confident that JPMorgan Chase can grow and earn a good return for its shareholders, the competition will be intense, and we must get faster and be more creative.

1. Banks are playing an increasingly smaller role in the financial system.

In the chart below, you will see that U.S. banks (and European banks) have become much smaller in size relative to multiple measures, ranging from shadow banks to fintech competitors and to markets in general.

Read footnoted information here

Whether you look at the chart above over 10 or 20 years, U.S. banks have become much smaller relative to U.S. financial markets and to the size of most of the shadow banks. You can also see the rapid growth of payment and fintech companies and the extraordinary size of Big Tech companies. (As an aside, capital and global systemically important financial institution (G-SIFI) capital rules were supposed to reflect the economy’s increased size and banks’ reduced size within the economy. This simply has not happened in the United States.)

Some regulators will look at the chart above and point out that risk has been moved out of the banking system, which they wanted and which clearly makes banks safer. That may be true, but there is a flip side – banks are reliable, less-costly and consistent credit providers throughout good times and in bad times, whereas many of the credit providers listed in the chart above are not. More important, transactions made by well-controlled, well-supervised and well-capitalized banks may be less risky to the system than those transactions that are pushed into the shadows.

2. The growth in shadow and fintech banking calls for level playing field regulation.

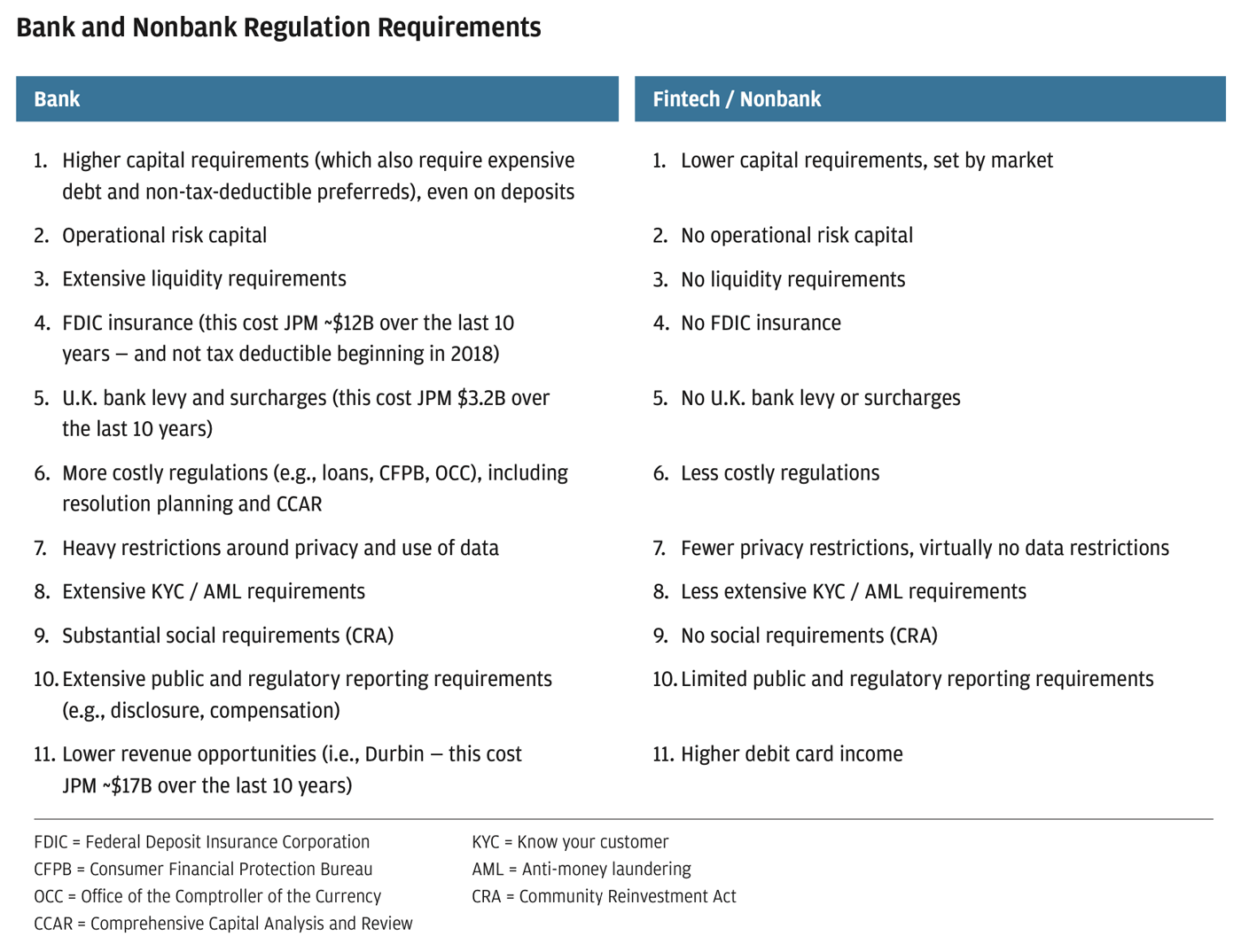

The chart below shows the potential regulatory differences between being a bank and being a nonbank or a fintech company – though this varies for each type of company on each item depending upon its legal and regulatory status. In some cases, these regulatory differences may be completely appropriate, but certainly not in all cases.

When I make a list like this, I know I will be accused of complaining about bank regulations. But I am simply laying out the facts for our shareholders in trying to assess the competitive landscape going forward.

It is completely clear that, increasingly, many banking products, such as payments and certain forms of deposits among others, are moving out of the banking system. In addition, lending in many forms – including mortgage, student, leveraged, consumer and non-credit card consumer – is moving out of the banking system. Neobanks and nonbanks are gaining share in consumer accounts, which effectively hold cash-like deposits. Payments are also moving out of the banking system, in merchant processing and in debit or alternative payment systems.

We believe that many of these new competitors have done a terrific job in easing customers’ pain points and making digital platforms extremely simple to use. But growth in shadow banking has also partially been made possible because rules and regulations imposed upon banks are not necessarily imposed upon these nonbanks. While some of this may have been deliberate, sometimes the rules were accidentally calibrated to move risk in an unintended way. We should remember that the quantum of risk may not have changed – it just got moved to a less-regulated environment. And new risks get created. While it is not clear that the rise in nonbanks and shadow banking has reached the point of systemic risk, this trend is accelerating and needs to be assiduously monitored, which we do regularly as part of our own business.

A few items need further explanation. On capital requirements, you should always remember that the market determines this level, not regulators, and to the extent that capital requirements in one entity are much higher than another, activities will move. Ironically, because standardized capital and G-SIFI capital do not recognize credit risk, banks have a peculiar incentive to hold higher risk credit rather than lower risk credit. All companies have operational risk, and most companies absorb operating losses through earnings. Banks are required to hold substantial capital against this risk. (I’m not debating that there is operational risk.) And because of the Durbin Amendment, if a bank has a customer with a small checking account who spends $20,000 a year on a debit card, the bank will only receive $120 in debit revenue – while a small bank or nonbank would receive $240. This difference may determine whether you can even compete in certain customer segments. It’s important to note that while some of the fintechs have done an excellent job, they may actually be more expensive to the customer.

Finally, it’s important to point out that not only has private credit been moving to the private markets but so have companies themselves. The number of public companies in the United States has been dropping dramatically over the past two decades, which has corresponded to an even larger increase in the number of private companies. Following its peak at 8,000 in 1997, the number of public companies is now around 6,000, and if you exclude non-operating companies, such as investment funds and trust companies, the decline is even more dramatic. This is worthy of serious study. The reasons are complex and may include factors such as onerous reporting requirements; higher litigation expenses; annual shareholder meetings focused on matters that most shareholders view as frivolous or inappropriate for company actions; costly regulations; less compensation flexibility; and heightened public scrutiny. It’s incumbent upon us to figure out why so many companies and so much capital are being moved out of the transparent public markets to the less transparent private markets and whether this is in the country’s long-term interest.

We need competition – because it makes banking better – and we need to manage the emerging risks with level playing field regulation in a way that ensures safety and soundness across the industry.

3. AI, the cloud and digital are transforming how we do business.

We cannot overemphasize the extraordinary importance of new technology in the new world. Today, all technology is built “cloud-enabled,” which means the applications and their associated data can run on the cloud. This brings many extraordinary advantages, but the one that I’d like to spotlight is the immediate ability to access data and associated machine learning with virtually unlimited compute power. Essentially, in the cloud, you can “access” hundreds of databases and deploy machine learning in a split second – something mainframes and legacy systems and databases simply cannot do. To go from the legacy world to the cloud, applications not only have to be “refactored,” but, more important, data also must be “re-platformed” so it is accessible. This availability of data – and banks have a tremendous amount of data – makes data enormously valuable and digitally accessible. All of this work takes time and money, but it’s absolutely essential that we do it.

We already extensively use AI, quite successfully, in fraud and risk, marketing, prospecting, idea generation, operations, trading and in other areas – to great effect, but we are still at the beginning of this journey. And we are training our people in machine learning – there simply is no speed fast enough.

4. Fintech and Big Tech are here…big time!

Fintech companies here and around the world are making great strides in building both digital and physical banking products and services. From loans to payment systems to investing, they have done a great job in developing easy-to-use, intuitive, fast and smart products. We have spoken about this for years, but this competition now is everywhere. Fintech’s ability to merge social media, use data smartly and integrate with other platforms rapidly (often without the disadvantages of being an actual bank) will help these companies win significant market share.

Importantly, Big Tech (Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google – and, as I said, now I’d include Walmart) is here, too. Their strengths are extraordinary, with ubiquitous platforms and endless data. At a minimum, they will all embed payments systems within their ecosystems and create a marketplace of bank products and services. Some may create exclusive white label banking relationships, and it is possible some will use various banking licenses to do it directly.

Though their strengths may be substantial, Big Tech companies do have some issues to deal with that may, in fact, slow them down. Their regulatory environment, globally, is heating up, and they will have to confront major issues in the future (banks have faced similar scrutiny). Issues include data privacy and use, how taxes are paid on digital products, and antitrust and anticompetitive issues – such as favoring their own products and services over others on their platform and how they price products and access to their platforms. In addition, Big Tech will have very strong competition – not just from JPMorgan Chase in banking but also from each other. And that competition is far bigger than just banking – Big Tech companies now compete with each other in advertising, commerce, search and social.

5. JPMorgan Chase is aggressively adapting to new challenges.

As tough as the competition will be, JPMorgan Chase is well-positioned for the challenge. But our eyes are wide open as the landscape changes rapidly and dramatically. We have an extraordinary number of products and services, a large, existing client base, huge economies of scale, a fortress balance sheet and a great, trusted brand. We also have an extraordinary amount of data, and we need to adopt AI and cloud as fast as possible so we can make better use of it to better serve our customers. We need to make our extraordinary number of products and services a huge plus by improving ease of use and reducing complexity. We need to move faster and bolder in how we attack new markets while protecting our existing ones. Sometimes new markets look too small or appear not to be critical to our customer base – until they are. We intend to be a little more aggressive here.

While we will argue for a level playing field, both in terms of how products and services are treated by regulators and possibly how competition should be treated across platforms, we are not relying on much to change. So we will simply have to contend with the hand we are dealt and adjust our strategies as appropriate.

We have mentioned that our highest and best use of capital is to expand our businesses, and we would prefer to make great acquisitions instead of buying back stock. We are somewhat constrained by how much we can grow our balance sheet because our capital charges will grow with our size, so sometimes buying back stock may still be the best option. But acquisitions are in our future, and fintech is an area where some of that cash could be put to work – this could include payments, asset management, data, and relevant products and services.

We will continue to do everything in our power to make JPMorgan Chase successful – and are confident we can do so.

The full letter can be read here