By Jonathan Rick, Director of Research, Tradeweb

Fiscal shocks have a way of accelerating policy and structural change. To meet the economic challenge of the coronavirus pandemic, the European Union boldly moved forward plans to issue bonds on behalf of its member countries, achieving a level of funding coordination it may have taken years to reach without the crisis.

Jonathan Rick, Tradeweb

Jonathan Rick, Tradeweb

For investors, a natural question arises from this new centralized approach to selling what could amount to €850bn of debt: Will these new common bonds[1] - backed by the full faith and credit of the European Union - undercut or enhance liquidity in the individual member countries' securities?

On the face of it, there are two broad possibilities. It would seem logical that big supply from a triple-A-rated “quasi-government” borrower could crowd out Eurozone governments’ bonds and sap their market liquidity. Investors could be attracted to the overall balance sheet of the confederation’s governing body and substitute EU bonds for other rates bonds in their portfolios.

https://twitter.com/Tradeweb/status/1367820063840034817

Or, maybe this tighter coordination of funding from the EU will have a halo effect, supporting liquidity for all countries’ bonds, as investors interpret this EU backstopping for member countries as positive for their credit and a source of much-needed economic relief.

In the last of our current series on issuance, Tradeweb built a data model to explore the question. What we found was the latter: that particularly for bonds of the Southern bloc countries – Spain, Greece, Italy and Portugal – the announcement of the EU funding program has had a significant positive effect on liquidity.

The Analysis

To do the analysis, we focused on benchmark 10-year debt across issuers, as this is the part of the curve that would be most reflective of the interaction between overall macroeconomic conditions, monetary policy and fiscal borrowing. Using bid/offer spread[2] as a proxy for liquidity, we tested the closing spread (monthly trimmed mean[3]) as a function of the following factors[4]:

- Realized monthly volatility of the given country’s 10-year benchmark (i.e., macro conditions)

- European Central Bank monthly purchases prorated for the given country[5] (i.e., ECB monetary policy)

- A dummy variable that is 1 starting in August 2020 – just after the EU Recovery Fund announcement - and 0 otherwise[6] (i.e., EU fiscal borrowing)

On volatility, we’d naturally expect a positive correlation with bid/offer spread; the higher the uncertainty of the true price, the higher the cost for liquidity.

We also assumed that when the ECB is actively buying individual country bonds in a given month, it should be supportive of liquidity as a backstop buyer. Bid/offer spreads on that country’s bonds should narrow when the ECB is more active.

Finally, and importantly, announcement of the new EU debt program brought clarity to how proceeds from a centralized EU approach would benefit member countries. The loans and grants proscribed under the program would fund member country social and economic needs, therefore likely reducing member countries’ individual market funding needs while also lowering their average cost of funds.

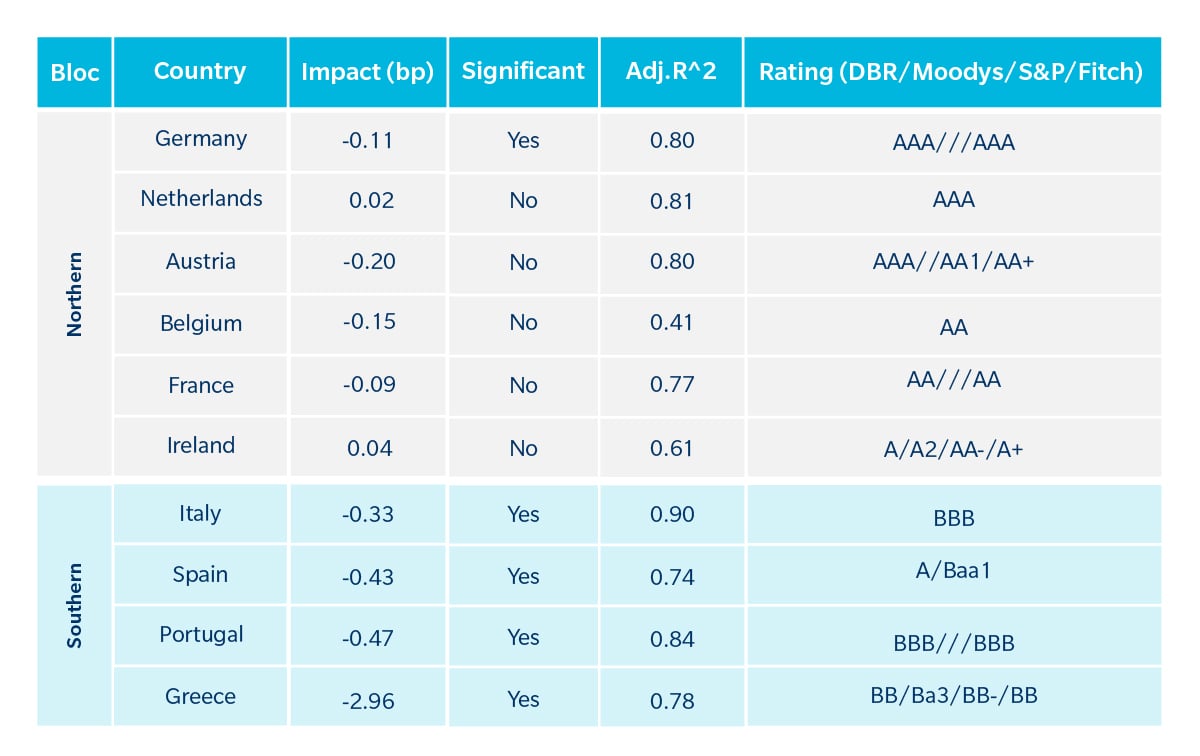

Each of these factors proved statistically meaningful (significant) to a tightening of bid/offer spreads in the Southern countries that we mentioned above. That tightening was about 0.3-0.5 basis points for Spain, Italy and Portugal. For Greece it was more than 2bp.

Figure 1 – Model Results

Impact reflects the beta of linear regression model of the dummy variable described above.

A negative number reflects a tightening of bid/offer spread.

Significance of dummy variable based on p-value < 0.05

Jan 2019-Feb 2021

Surprisingly, bid/offer spreads on German bonds also responded, by about 0.1bp, which could possibly be explained by Germany’s status as an EU bellwether and because of the potential benefits an EU financial support plan could bring to Europe overall.

For the other Northern countries that we included in our analysis – Austria, Belgium, France, Ireland and the Netherlands – the EU announcement had little effect on bid/offer spreads for their bonds from a statistically significant standpoint. All rated single-A to triple-A, these countries are generally in a stronger economic position than their lower-rated Southern neighbors and therefore likely better positioned to weather the crisis on their own. Similarly, the model suggested that most of these countries were also not impacted by monthly ECB purchases, which suggests its backstop has limited impact on current liquidity conditions of these bonds.

If the EU had hoped that coordinated and centralized funding would support fragile economies in Europe during the coronavirus pandemic, improve financial conditions and support liquidity in bonds of its member states, one could already argue that the initiative has been a success. Judging by the data, markets – usually the best arbiter of risk – see the EU bonds’ presence as a net positive for sovereign debt in the region.

Source: Tradeweb

[1] The announced €750 in EU Recovery Fund bonds as well as the previously announced €100 in EU SURE bonds

[2] Bid/offer spreads based on end-of-day Tradeweb composite yields for 10-year benchmark bonds

[3] As the analysis looks at monthly aggregate data, we wanted to reduce the impact of a single significant outlier that might excessively skew the data, particularly given that bid/offer spreads are bounded by 0 on the left-side of the distribution and theoretically unbounded on the right.

[4] Specifically the model was an OLS regression for each country of bid/offer spread ~ N(realized vol) +N(ECB purchases) + dummy variable, where N(*) is the z-score

[5] The ECB’s PSPP breakdown by country was added to the ECB’s monthly PEPP, prorated based on the percentage of cumulative public sector purchases under the program allocated to the given country.

[6] In the recent crisis, markets saw appreciable liquidity improvements simply following the announcement of a new program or facility, even before it was put into effect. That was true, for example, with the U.S. Federal Reserve’s announcement of its new corporate credit facilities, as discussed here: https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/10/the-impact-of-the-corporate-credit-facilities.html